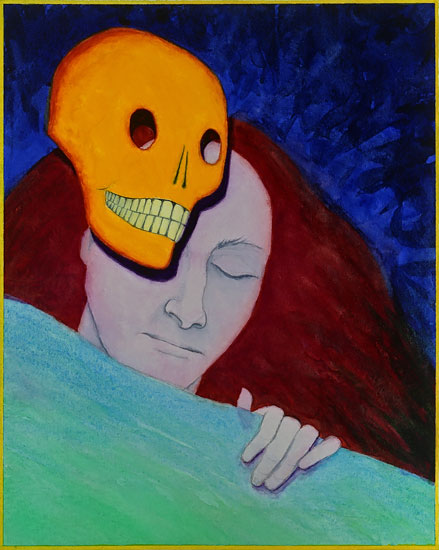

Watercolor sketch I did on a trip to Mexico Jim and I took in 1990. I painted and he wrote a history book.

Here’s the second of three Boarder stories chopped out of my novel. She’s talking to my young narrator, Brooklyn.

“Did I ever show to you a picture of my boychik?” the Boarder asked. “He’s a regular Elvis, kayne horeh. Here, I have it right here.”

She whipped out a picture album with a mahogany cover carved with the words, “Eternal Memories,” and flung it open on the table to a crumbling, yellowed newspaper clipping with a caption in Spanish. “Nu? Here he is.”

“This one?” I pointed. “The man with the high forehead and little round eyeglasses?”

“Noooo, of course not,” she said, waving her hand. “That? That’s the famous communist, Leon Trotsky. A regular trouble-maker. Every Monday and Thursday with a revolution. And chutzpa? You don’t know from it.”

“Is it this one, this big guy?”

“Noooo,” she said again, smacking her forehead. “That’s the famous Diego Rivera, a meshuga artist. The class struggle this, the class struggle that, but when he paints a picture, you can’t miss it. He even painted one in New York, a mural in Rockefeller Center. Don’t even ask, with Lenin smack in front. Only in America.”

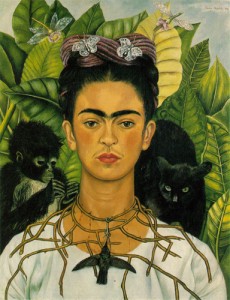

“Well, then,” I said, “the only one left is this lady with the big eyebrow.”

“Her? Hau boy. You know who she is? Okay, okay already, I’ll tell you. That’s Frida Kahlo. Also a famous artist. Arty-shmarty, native-shmative, there’s nothing wrong with her a tweezers wouldn’t fix. Anyway, I know her tata, an Ashkenazi Jew like us. In the wholesale pickled hot tamale business he’s in. I knew him on the Lower East Side. America, it wasn’t good enough for him. Mexico he needed. Also with the big eyebrow. The daughter, Frida? She’s a Mexican Indian like I’m a Mexican Indian. But can she paint a picture!”

“So where’s your son? There’s no one left.”

“My boychik? He’s right here.” She tapped the clipping.

“You mean this grey blur? That’s a person? You sure?”

“Sure I’m sure. You think a mama wouldn’t recognize her own flesh and blood, who she worked and slaved over, and broke out of jail? That’s him, behind Diego. Look at those sheyneh green eyes. Later he saved Troksky’s life.”

“He saved Troksky’s life?”

“Brookileh.” She pinched my cheek. “You think I’m the only one who ever farpotshket with fate? Predetermined time-line? Hau boy! An accident waiting to happen.

“Anyway, everyone knows how the, feh!, Stalinists attacked Trotsky, with his wife and grandson. In the middle of the night they came, must have been twenty or thirty of them, dressed up like police. They schmoozed their way in, tied up the guards, and shot two or three hundred bullets into the Trotskys’ bedroom. Then, just to make sure, they threw in a few bombs. Nobody could have survived.

“Afterward they patted each other on the backs, congratulating themselves on an assassination well-done, all the Trotskys nice and dead, Stalin nice and happy.

“What nobody knows, is what happened earlier. That night, my boychik… he’s so charming. Charming like me.” She grinned and batted her eyelashes. “Earlier that night, my boychik is checking around the courtyard of the Trotskys’ famous walled House in Mexico, and who does he see, but Molech ha-movess.”

“The Angel of Death!” I cried. “He can see him too?”

“Of course. It runs in the family. ‘Buenos noches,’ my boychik says, turning on the charm like a fire-hose. Who could resist?

“‘I know you from somewhere, don’t I?’ the molech asks. He puts on his eyeglasses and squints. But before he knew what hit him, my boychik’s taking him for a drink in some nightclub with swinging doors and dancing ladies.

“They slug back for themselves a few mescals with worms, and then the Molech says, ‘I don’t know why, but when I look at you the name Malky Levine comes to mind. I think it’s your eyes. That odd moldy-green color. Malky Levine, Malky Levine, Malky Levine. Who could that be?’

“‘Who could that be!’ my boychik yells. ‘That’s my mama! I know why you know me. You must have heard about the jail break.’

“‘No,’ says the molech. ‘Never heard of it.’ So my boychik he tells him the whole story and that’s that. So how’s about some five-card stud?”

“Not now!” I cried. “You’re in the middle of a story.”

“What?”

“Molech ha-movess. What did he say when your son finished the story about the jail break?”

“What did he say? Ay-yay-yay. He looks at his watch, then all of a sudden he screams, ‘SNAIL SLIME! Look what time it is! I was supposed to take the Trotskys an hour ago.’ Then he grabs his head and moans. ‘My fourth big mistake! I’ll be demoted to cockroaches. Or worse yet scorpions. Did you know scorpions don’t age? They never die!’”

“What happened to the Trotskys?” I asked.

“The molech, still in the girlie club, says. ‘Who’s next?’ He gives a look in his ledger. ‘Gotta run.’ He heads for the door. ‘It’s rush hour in New Jersey and after that some epidemic in India.’

“So my boychik, he heads back to the Trotsky’s House. From outside he hears a boychik saying, ‘No I have more, a hundred at least,’ then a lady’s voice, ‘Beats mine, only fifty-five.’

“He opens the front gate and gives a look. All the doors and windows are blown out, and the pet bunnies got loose and are hopping around. The guards and guests are sitting in the garden. It’s a regular garden party, and the gansa Trotsky family are walking back and forth on the patio counting bullet holes in the walls. They didn’t even have scratch on them, kayne horeh.” She winked at me. “They say they saved themselves by jumping under their beds.”

A recreation by Diego Rivera of Man at the Crossroads, his mural that was almost in Rockefeller Center. Amazingly, it included Lenin leading the oppressed masses. Even more amazingly it was commissioned by Nelson Rockefeller. Not so amazingly, he suddenly remembered who he was and had it torn down before it was finished.

The story of how the Trotsky’s saved themselves is pretty true. Google it. For the jailbreak story please see the previous blog post.

Below is a rendition of the Internationale. I’m not a communist myself, but has there ever been a more rousing anthem? It’s almost enough to make you want to run out and join the Russian revolution.

4 comments